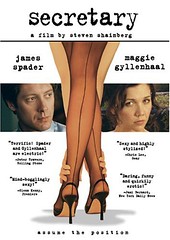

When I recently watched Stephen Shainberg’s Secretary (2002) I was abruptly reminded of a movie of the early 1940’s, Frank Capra’s Meet John Doe. I was completely taken aback by the connection: Meet John Doe is the only other movie I can remember seeing which confronts the issue of an adult male spanking an adult female. But there are other connections as well, involving Christian iconography, issues of ‘punishment’, and definitions of love, worthiness, and womanhood. The two films are worthy of a comparison.

Granted, the 1941 version of spanking in Meet John Doe is given artistic distance both by being presented in the context of a dream and being described rather than dramatized. Secretary includes spanking too. Secretary was marketed as a comedy, and I suppose it is in the sense that it has a happy ending for our sadomasochistic lovebirds. But the giggles this movie produces are probably from discomfort or embarrassment, rather than humor. Secretary is not funny, it is romantic: like Meet John Doe, it is first and foremost a love story.

Maggie Gyllenhaal stars as Lee Holloway, a girl who has just been released from a mental institution because of her self-injury practices. She is a girl who cuts herself, and this self-immolation seems most directly triggered by the alcoholism of her father. When Lee’s father is drunk, Lee is most likely to cut herself. Most poignant is the implement kit Lee uses for her practice: a pre-teen’s jewelry box, covered with butterflies and ballerinas, it belies both her youthful innocence and her long endurance of self-wounding.

She goes to secretarial school, getting top-marks in typing, and goes to work for E. Edward Grey, an attorney. Grey is clearly a control freak with more than a personnel problem. His “secretary wanted” vacancy sign lights up like cheap motel neon. He raises orchids and safe-traps mice; he is impeccably dressed and has perfect posture. It ultimately comes as no surprise that he is a spanker and a dominator.

But all the reviews I have read of this film leave out Grey’s most important quality. Before he becomes Lee’s dominator, he becomes her Father confessor. He sees the Band-Aids covering her legs and very gently broaches the subject. Lee, very embarrassed, acknowledges her practice but says she does not know why she does it. “Is it,” Grey says, “that sometimes the pain inside has to come to the surface and when you evidence of the pain inside you finally know you’re really here? Then when you watch the wound heal, it’s comforting, isn’t it?” He gives her hot chocolate, the perfect drink for sensual absolution, and then he concludes her confessional with this paraphrase of a priest‘s admonition, “go, and sin no more.”

I’m going to tell you something, Lee. Are you ready to listen? Are you listening? You will never, ever, cut yourself again. Do you understand? Have I made that perfectly clear? It’s over now. It’s in the past. Never again.

Grey’s analysis of Lee’s motives may be pop-Freudianism, but within the context of this film his absolution is critical. It is essential to this story that Lee’s sub/dom relationship with Edward is not the cure for Lee’s self-injury. Soon to follow is Lee’s epiphany, which points directly to this issue. Mr. Gray sends Lee on a walk, free from her mother’s oppressive daily car ride home, free from self-abuse, free from sin. Her words show directly that not only is she healed but also that the relationship to follow is not the cause of the healing.

…it was as if I had never taken a walk by myself…but because he had given me permission to do this, because he’d insisted I do it, I felt held by him as I walked along…The next day I didn’t even bring my cuticle scissors and my iodine, but I did make another typing mistake…

And only then do the “games” begin. Lee’s pleasure in punishment from Grey is not the same as her self-injury, and Grey “insists” that this is in the past before he begins domination games with her.

Meet John Doe gives us a different kind of Christian iconography, but one that also grows directly out of the love relationship within the picture. Long John Willoughby, played by Gary Cooper, has been shown in numerous reviews to be a Christ-figure.# He rises from obscure humble beginnings to speak the truth, is betrayed by everyone, and expects in the end to sacrifice his life for his message. (One very nice touch I uncovered in researching this paper is that John’s betrayal, when he is denounced as a fake at the John Doe Convention, takes place in Chicago’s Wrigley Field. John Willoughby, on a constructed stage, is of course in the center of the structure, directly on top of the pitcher’s mound, where he has said throughout the movie he wants to be. #) But if John is a Christ figure, what does that make Ann Mitchell, John’s love interest played by Barbara Stanwyck? After all, it is her talent for story writing that creates the John Doe myth in the first place. (The images of her typing the John Doe letter: fast, powerful, and determined, are in stark contrast to Secretary’s typing, which is a regressive anti-technology imposed by Grey for subversive purposes.) Ann picks Willoughby out of the mass of hobos who “apply” for the job, and she creates his message based on the precious (and I mean that in both senses of the word, valuable and affected) writings of her own dead father.

She admits that she has “fallen in love” with the idealized John Doe she has created, without connecting that man to Willoughby, at least not yet. So who is Ann? A casual observer might see her as a Judas Iscariot, the one who betrays Christ for thirty pieces of silver (she says money is her primary motivation), but actually in every single facet of the story she is the Apostle Peter. It will come as no surprise to a theologian watching this film that Ann “denies” Willoughby, overlooks and rejects the idea of a love relationship with him, three times: first immediately after the ‘spanking’ dream, second on the airplane ride during John Doe’s speaking tour, and finally in DB Norton’s mansion, where she reluctantly accepts a fur coat and diamond bracelet before realizing the evil that Norton intends. Ann’s epiphany is brought about then, as John Doe crashes the meeting and tells Norton off. Like Peter with Christ, Ann learns after the betrayal that she loves this man and that his mission is her mission, too. “The cock crows,” and she is devastated by her betrayal of her Christ figure.

The mission that ultimately unites Ann and John is for Frank Capra a religious mission, a combination of Capra’s Catholicism and Americanism. In order to understand this mission, it is necessary to understand the evil that Norton represents and that Ann and John ultimately must fight together. Unlike many of Capra’s comedies of the thirties, Meet John Doe has as the enemy not the wealthy, as in It Happened One Night or Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, or the politicians as in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, but the anti-democratic thugs who represent the secretive, evil, and ultimately fascist D.B. Norton. In Meet John Doe there is no dividing-line between Christianity and populist democracy. “The people” are the power, and that power is fed by and derived from distinctly Christian themes and constructs. Contrariwise, evil is represented by the desire for ultimate power that consciously does not derive from “the people.” D.B. Norton’s fascism is unadorned: “We are coming to a new order of things… What the American people need is an iron hand.” One particularly insightful review# points out that Norton represents a trilogy of evil in Capraville: big business, big media, and big government. Capra’s purpose in making this film was to counteract the currents of fascism beginning to infect American public discourse in 1940, and Capra goes so far as to use Nazi-like motorcycle storm troopers and thugs to do Norton’s bidding, haunting reminders that the dangers which engulfed Germany reside in America, too.

Ironically, church and religion itself are not portrayed in this film. Because Capra is seeking to unite the “little guys,“ he has no use for individual denominations. Instead, “John Doe Clubs” are formed, and Christmas, the most secularized and universal of Christian holidays, is held up as the ideal of these clubs at both at the beginning and at the apparent end of John Doe’s career. Willoughby’s opening speech on the radio provides this secular instruction:

Your neighbor - he's a terribly important guy, that guy next door… If he's sick, call on him. If he's hungry, feed him. If he's out of a job, find him one… I know a lot of you are saying to yourselves: 'He's askin' for a miracle to happen…' Well, you're wrong. It's no miracle. It's no miracle because I see it happen once every year and so do you at Christmastime. There's something swell about the spirit of Christmas, to see what it does to people, all kinds of people. Now why can't that spirit, that same warm Christmas spirit last the whole year round? Gosh, if it ever did, if each and every John Doe would make that spirit last 365 days out of the year - we'd develop such a strength, we'd create such a tidal wave of good will that no human force could stand against it.

The end of Meet John Doe not only reinforces the Christian/Christmas iconography of the film, it brings us back to Secretary and the common and contrasting qualities of Ann Mitchell and Lee Holloway. It is remarkable that at the end of these very different films these two very different women are saying essentially the same thing to their male love object: I love you, we can start over, and here is the way our world will look, here is how we can make it work. Ann Mitchell’s impassioned words as John contemplates jumping off the top of City Hall, promise John that his suicide is not only wrong, it is unnecessary. Her speech is the culmination of the secularized Christian values of the film, as well as a profession of love and true devotion both to John Willoughby and the John Doe ideal she created:

We'll start all over again. Just you and I. It isn't too late. The John Doe movement isn't dead yet. You see, John, it isn't dead or they [Norton's group] wouldn't be here. It's alive in them. They kept it alive by being afraid. That's why they came up here. Oh, darling!...We can start clean now. Just you and I. It'll grow John, and it'll grow big because it'll be honest this time. Oh, John, if it's worth dying for, it's worth living for. Oh please, John...You wanna be honest, don't ya? Well, you don't have to die to keep the John Doe ideal alive. Someone already died for that once. The first John Doe. And he's kept that ideal alive for nearly 2,000 years. It was He who kept it alive in them. And He'll go on keeping it alive for ever and always - for every John Doe movement these men kill, a new one will be born. That's why those [Christmas eve] bells are ringing, John. They're calling to us, not to give up but to keep on fighting, to keep on pitching. Oh, don't you see darling? This is no time to give up. You and I, John, we...Oh, no, no, John. If you die, I want to die too. Oh, oh, I love you. [She passes out from sickness and grief.]

Lee, in a moment reminiscent of

The Graduate, runs away from a bridal dress fitting and marriage to her dull boyfriend, into Grey’s office. “I love you,” she says in her wedding dress. Grey does not believe her, cannot believe that someone would want to be treated the way he wants to treat her, as a dominant. “We can’t do this 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” he says. “Why not?” she says. And then she issues a physical and verbal challenge to him: she sits at his desk, looks him in the eye and says, “I want to make love.” Needless to say, this is not a submissive act. She has taught herself the rules of the game (she listens to sub/dom self-help tapes and uses “time-out” as her safe word) and now she insists to Grey (who true to his name has been ambivalent about his feelings and actions) that he play for real.

He takes up the gauntlet in yet another brilliant example of Christian iconography. She is to keep her hands on his desk and her feet on the floor until he comes back. Grey’s office, which has been a church, a dungeon, and a Garden of Eden, now becomes a tomb. Three days in the tomb is where Christ was, and it is where Lee will stay, faithful and loving, until her savior and master returns. He returns after three days with more chocolate drink, this time a milkshake, his cup of vinegar, cold and reviving. He carries her up to the second floor of his building, which we have not seen before, and after baptizing her body in a cleansing bath, gives her redemption: they make love.

We learn in her voiceover that she describes all of her scars in chronological order to Grey, and that for the first time she feels beautiful. Her suffering is not for naught. Her thin body, lying on a bed of grass, with overtly symbolic symmetrical scars across her ribcage, recalls completely Renaissance portraits of the Passion. Without irony, her passion is completed.

A wonderful thing about this movie is its unpredictability. As he kisses her body, she asks him personal questions about his childhood. “What was your mother like? What did it say under your high school yearbook photo?” I found this a very tense moment. Would her post-coital attempt at gentle intimate pillow talk be punished? Is Grey a lover and playmate or a monster? He answers her last question: “Where were you born?” “Des Moines, Iowa.” Ah, she is safe. He is from Capraville. The man who will not harm a mouse in his office will not ever harm her.

Let’s end this post with ruminations about spanking. The contrast between these two women and the way spanking is used in these films says a great deal about womanhood and sexuality. As I said in the beginning of this paper, the spanking in Meet John Doe is rendered safe by being in a humorous and described rather than enacted dream sequence. The description is also given in a rather hayseed fashion by Gary Cooper:

“I dreamt I was your father. There was something that I was trying to stop you from doing…you were getting married [Ann looks up and freezes] …And then I knew what it was that I was trying to stop you from doing. Dreams are sure crazy, aren't they? Well, would you like to know who it was you were marrying? ...It was that fellow who sends you flowers every day. What's his name - Mr. Norton's nephew? ... Well, I took you across my knee and I started spanking you. That is, I didn't do it. I mean, I did do it. But it wasn't me, you see. I was your father then. [John acts out her spanking] Well, I laid you across my knee and I said, 'Annie, I won't allow you to marry a man that's just rich [whacks his knee] or that has his secretary send you flowers [whack]. The man you marry has got to swim rivers [whack] for you, he's got to climb high mountains for you. Whack] He's got to slay dragons for you.[whack] He's got to perform wonderful deeds for you.' Yes sir, and all the time the guy up there, [the minister conducting her ‘marriage’] you know, with the book - me - stood there nodding his head. And he said, 'Go to it, Pop. Whack her one for me, because that's just the way I feel about it, too.' So he said, 'Come on down here and whack her yourself.' So I came down and I whacked you a good one...”

John’s dream of “spanking” Ann is a cloaked marriage proposal, the first time John actually reveals himself to her. I suppose a radical feminist would interpret it as threatening punishment for not adopting a traditional role of womanhood. But looking deeper we see that in John’s dream Ann is actually being spanked for running toward marriage, just to the wrong man. John takes on the authority of church (the only church in the film) and spanks Ann as well in order to get her to see reason. She must marry John because money alone is not worthy of her. In declaring a public spanking of Ann to be his dream, he is attempting to declare his frustration at his lack of control over her. Her complete, religious submission (she is willing to die if John does) at the film’s end is confirmation of the film’s values for both women and citizens of God’s country.

The spanking in Secretary is altogether different: it is role-playing, sensual, punishing, real. It is not a dream. Throughout this movie we see the graphic result of Grey’s actions: Lee’s red buttocks, Grey’s sperm on her blouse, etc. This is really happening, and she likes it. She accepts this lifestyle before Grey does, and she leads him to the life they will have together: they are married in a June wedding, and she’s a homemaker. Well, she’s a homemaker with a dead roach in her pocket, to place on their perfectly made bed so that she may be “punished” later: the submissive invites and thus controls the situation. They are happy, and since we have seen the suffering both these kind people have suffered, we celebrate with them their liberation. Their liberation is this: a marriage both domestic and traditional on the outside (his goodbye and off to work at the end of the movie is a conscious reflection of Pleasantville, The Truman Show, and other post-modern “idealized” domestic scenes which of course, lean heavily on Capra) and as she declares when Lee stares at the camera with a beautiful half-smile in the film’s last scene, the inside of their marriage is their own happy business.